Introducing Jacob Bradford

Our 2nd great-grandfather and his family

Introducing Jacob Bradford

By Bobbi Spiker-Conley

Every year my parents surveyed several family grave sites. Daddy could be found cutting grass with his scythe while Mother would be raking debris. Pictured below is my father tending his grandparents’ graves (Isaac Monroe & Catharine Davis Bradford Spiker) at the Indian Creek Baptist Cemetery in Washburn, WV. To the right of their headstone is the Civil War memorial that Brad Spiker ordered for Catharine’s father, Jacob Bradford. But he isn’t there. We have no idea where his body lies at rest.

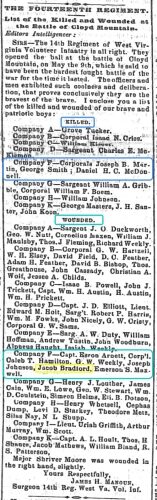

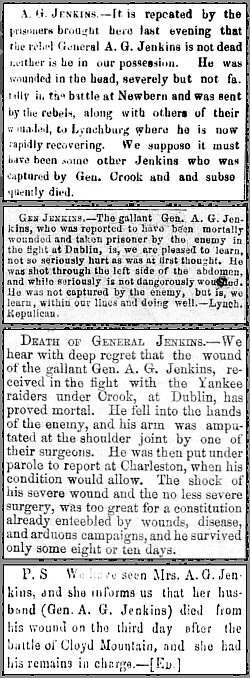

The Wheeling Daily Intellingencer,

The Wheeling Daily Intellingencer,

Tuesday, June 14, 1864

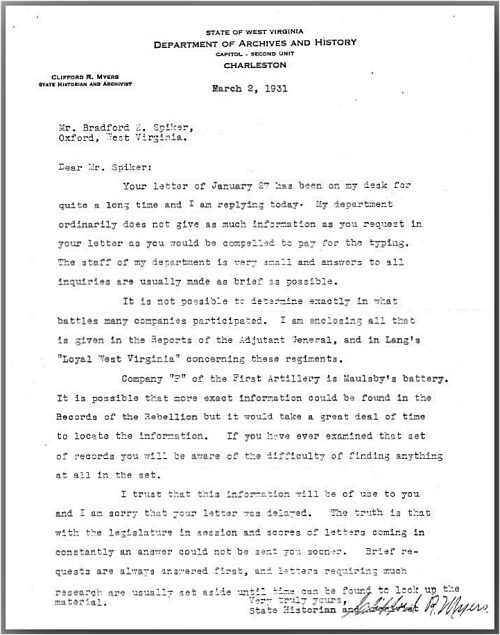

In January 1931, Brad Spiker sent a request for information to the WV Department of Archives and History in Charleston. Based on the response that he received two months later from State Historian and Preservationist, Clifford R. Myers, Uncle Brad must have asked a few too many questions (just like any investigative genealogist would do, right?) Fortunately, they provided relevant photocopies from the Adjutant General’s Reports and Lang’s Loyal West Virginia (to which I’ve linked below.)

From the Adjutant General’s Reports

List of changes that have taken place since organization

- Page 373 - Fourteenth Regiment W.VA. Infantry Volunteers, beginning with Company “A”

- Page 386 - End of Company “E”, beginning Company “F” – Jacob Bradford listed as a Private

- Pages 398 thru 400 - Memoranda: Fourteenth Regiment organization & list of battles

List of recruits since date of returns published in report for 1864

-

Page 209 – Fourteenth Regiment W.Va. Infantry Volunteers, beginning with Company “A”

List of deaths, discharges, and desertions of enlisted men from date of original organization to date of muster out on 26 June 1865. - Page 211 – Fourteenth Regiment W.Va. Infantry Volunteers, beginning with non-commissioned staff

- Page 215 – End of Company “E”, all of Company “F” – Jacob Bradford listed here as “Died in hands of enemy from wounds rec’d in action at Cloyd Mt., May 9, ‘64.”

From Loyal West Virginia from 1861 to 1865

- Page 291 thru 295 - Roster of Field, Staff and Company Offers of Fourteenth Regiment showing alterations & casualties to date of muster out. Stories. Battles.

Sadly, we do not have much information about him at all. The only known photograph of Jacob Bradford comes from my mother’s genealogy records. Her notes neither indicate a source nor where the original may be located. The quality of the copy is very poor but an attempt has been made to enhance some of the details (below, right.)

What we do know is that our 2nd great-grandfather, Jacob Bradford, died from wounds received at the Battle of Cloyd’s Mountain (aka Cloyd’s Farm.) His wife, Nancy (Davis) Bradford, mourned his loss along with their four children, 9-year-old Dennis, 7-year-old Rebecca Ann, 5-year-old Catharine (grandpa Jake’s mother,) and 2-year-old Emeline.

What we do not know for certain is where he died or what happened to his body. His military records are ambiguous. All of the reports agree that he was wounded in the battle that occurred on May 9, 1864, and all but one agree that he died of those wounds on May 30, 1864. But the reports appear to disagree as to whether he died at Cloyd farm, in a hospital, or in a rebel prison.

Casualty Sheet – Was wounded and captured at Cloyd’s Mtn, May 9 1864, and died, in the hands of the enemy, May 30, 1864, while a prisoner of war.

Regimental Descriptive Book – Wounded at the battle of Cloyd Mtn. Va May 9 1864. Died in Rebel Prison June 27, 1864

Appears on Returns – May 1864 absent wounded at Cloyds Mountain and left there.

Claim for Minor’s Pension – Died on 30 May 1864 of wounds received in action.

Claim of Guardian of Orphan Children for Pension – Died at Cloyd farm Virginia on or about the thirtieth day of May 1864 by reason of a wound received at the battle of Cloyd Mountain Virginia.

Act of July 14, 1862 – (Eli Cline) Died at Cloyd Farm W. Va. May 30 1864 “wound”

Act of July 14, 1862 – (Nancy Bradford) Died at Cloyd Farm VA May 30 1864 wounds.

Claim for Widow’s Pension – The Adjt Gen reports that Jacob Bradford was mustered as a Private 30 August 1862, and died May 30 1864 of wounds received in action.

Widow’s Claim for Pension – Died in the hospital at Cloyd farm in the State of Virginia, in the hands of the rebels by whom he was captured while he was in said hospital on the 30th day of May A.D. 1864 of a wound received at the battle of Cloyd Mountain Virginia while in the line of duty in service of the United States.

To answer the question of where Jacob Bradford died, I started my research at the battle site — Cloyd’s Mountain, Virginia. The battle is often cited as being one of the most fierce and bloody battles in the entire Civil War. The savage fighting lasted only an hour, but the percentages of casualties were high for the relatively low number of troops: the Federals sustained 10% losses (with 688 killed, wounded, and captured) and the Confederates sustained 23% losses (with 538 casualties.) Captain Michael Egan of the WV 15th wrote, “The battle that ensued was one of the most destructive of the war, considering the time occupied and the numbers of the forces engaged. The general engagement did not last over forty minutes, and only about eight thousand men on both sides participated, but our losses included about 600 killed and wounded, and the enemy lost, perhaps, about 400. It has ever since been a wonder to me that the proportion of fallen combatants did not exceed one in eight of the whole number engaged.”

Never heard of that battle? You’re not alone. Over 10,500 military engagements occurred during the civil war. Most of us are familiar with the major battles (such as the first Battle of Bull Run, Shiloh, Antietam, Gettysburg, and Vicksburg, etc.) But, according to author Howard R. McManus, The Battle of Cloyd’s Mountain: The Virginia and Tennessee Railroad Raid, it “has lain shrouded in obscurity. Overshadowed by larger armies and more consequential campaigns, it failed to receive public recognition then, as it fails now. Most knowledge of the battle died with its veterans, who left only rare, scattered memoirs. As local tradition degenerated into error, the very battle site faded from memory.”

Scattered, too, are the resources dedicated to the battle — and, unfortunately, their data is contradictory — but I was able to visualize what transpired in the weeks leading up to our Great-Great-Grandfather’s death.

Organizing

In the summer of 1862, Jacob Bradford joined with other men from Pleasants, Ritchie, and Tyler counties to organize Company “F” of the Fourteenth WV Volunteers.

The 14th Regiment (comprised of ten Companies of men from Doddridge, Marion, Monongalia, Ohio, Pleasants, Preston, Ritchie, Tyler, and Wood counties) organized at Wheeling in August 1862. Until the Battle of Cloyd’s Mountain in 1864, only Company “A” had been involved in anything more than minor skirmishes and operations.

In April 1864, under order of Ulysses S. Grant, Union Brigadier General George Crook assembled three brigades of the West Virginia Army (see breakdown at right.) The 1st Brigade, from Charleston, would meet up with the 3rd Brigade, from Brownstown, then they’d march to Fayettesville, where the 2nd Brigade was in garrison, thereby completing Crook’s entire division.

The men in ranks didn’t yet know where they were headed, but after several dreary months of garrison duty, the men “little cared where, as we were tired enough of winter quarters and were anxious to be up and doing,” recalled Russell Hastings of the 23rd Ohio in his diary.

When the 1st Brigade formed line the morning of April 29 in preparation for their march, “a more joyous set of boys were never known. Cheer after cheer went up and when…the band struck up ‘Dixie’ all our hearts were stirred to their depths. But many a heart with us that morning within a few days ceased to beat, either on the skirmish or in bloody battle.”

Union - Kanawha Div. - Brig. Gen. George Crook

1st Brigade - Col. Rutherford B. Hayes

- 23rd OH Inf - Lt. Co. James M. Comly

- 36th OH Inf - Col. Hiram F. Devol

- Detachment, 34th OH Inf (attached to 36th OH)

- 5th WV Cavalry (Dismounted) - Col A.A. Tomlinson

- 6th WV Cavalry (Dismounted)

2nd Brigade - Col. Carr B. White

- 12th OH Inf - Col. J. D. Hines

- 91st OH Inf - Col. John A. Turley

- 9th WV Inf - Col. Isaac H. Duval

- 14th WV Inf - Col. Daniel D. Johnson

3rd Brigade - Col. Horatio G. Sickel

- 3rd PA Res. Reg. - Capt. Jacob Lenhart

- 4th PA Res. Reg. - Col R. H. Woolworth

- 11th WV Inf - Col. Daniel Frost

- 15th WV Inf - Lt. Col. Thomas Morris

Artillery - Capt. James R. McMillin

- 1st OH Battery - Lieut. G. P. Kirtland

- 1st KY Battery - Capt. David W. Glassie

The March

Sprawling 200 miles eastward from the Ohio River, the mountains of western Virginia posed an almost impassable barrier to human armies, McManus wrote. Lofty crests and plunging abysses precluded all but limited excursions across this landscape. Crook was undertaking a raid never previously attempted by infantry. The only thing that made the perils of this expedition worth the risks was gaining control of western Virginia’s supply lines. Their primary objective — destroy the track of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad as they advanced, then set fire to the 700-foot covered railroad bridge that spanned the New River at Central Depot (aka Newbern Depot, now the city of Radford.) It would require a forced march of six to seven days for Crook’s army to reach Central Depot; Confederates could reach the area by rail in less than one day.

After a long and bitter winter, the roads were in horrendous condition, muddied and blocked by fallen trees. And the out-of-shape soldiers, on their first days from winter quarters, winced from heavy knapsacks and aching feet as they attempted to clear paths for the wagons and artillery. The First Brigade was “thoroughly exhausted after fourteen miles, the soldiers were just as elated to fall out as they had been to fall in.” Then a ”cold winterish rain” increased the misery, stretching into the next day throughout another fifteen fatiguing miles. The “steady rain magnified to a drenching downpour by nightfall. Unavoidable prospects of sleeping on water-soaked earth loomed before the weary soldiers.”

Meanwhile, the Third brigade set out from Brownstown, tramping seventeen miles before making first camp. They met up with the First Brigade on Sunday, May 1, and bivouacked at Gauley Bridge. Three roads led across the mountains from Gauley Bridge. The first pointed toward Clarksburg. Another led to Lewisburg, Staunton and Lynchburg. The third wound southeastward toward Fayettesville, Raleigh, Princeton and across Virginia to the North Carolina border. Setting out the next morning, the combined troops began to cheer once more as the rain stopped and the column turned down the Fayettesville road. All now knew that their objective was the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad.

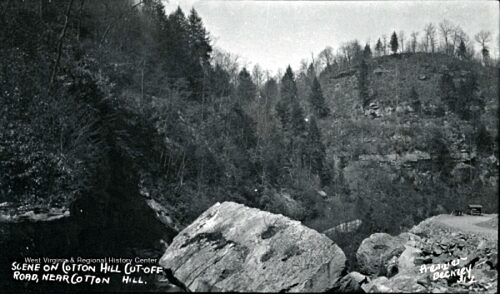

“The route to Fayettesville was seven miles over rugged Cotton Mountain. A system of alternate walking and resting increased the marching speed. The troops climbed as rapidly as possible for fifty minutes. At the sound of a bugle, the men then dropped to the grass without breaking ranks for a ten-minute rest. Aroused by a second bugle call, they arose and began again.” The day quickly became bright and warm. Soldiers grew excessively hot scaling the steep mountainside, and tossed blankets and overcoats to the roadside.

“The route to Fayettesville was seven miles over rugged Cotton Mountain. A system of alternate walking and resting increased the marching speed. The troops climbed as rapidly as possible for fifty minutes. At the sound of a bugle, the men then dropped to the grass without breaking ranks for a ten-minute rest. Aroused by a second bugle call, they arose and began again.” The day quickly became bright and warm. Soldiers grew excessively hot scaling the steep mountainside, and tossed blankets and overcoats to the roadside.

By late morning, the sky darkened, cold winds swept the mountain, and a heavy rain storm broke. “The steep path disappeared underfoot in a churning mass of mud. As the floundering troops climbed higher, the air grew colder and heavy rain turned first to sleet and then to snow. Clothing froze as the men advanced the last few miles huddled and bent before the driving storm. Finally attaining the summit, [the] exhausted soldiers … encamped in nearby woods. Without blankets or overcoats, the soaked and shivering men presented a ‘pitiful sight.’ The Second Brigade, already in garrison at Fayettesville, united Crook’s entire division.”

Snow fell rapidly as the troops pitched what few tents they had. Some regiments “had no tents, and didn’t want them on such a campaign,” Hastings recorded. “My duties as Adjutant-General required that I should be one of the first up in the morning and as I looked out of my tent this snowy morning I could only see the stacks of rifles where the regiment had placed them the night before, and innumerable hillocks of snow, each hillock representing a soldier soundly and warmly sleeping rolled in a blanket. At the first tap of reveille these hillocks suddenly turned into a living army,” as men brushed and shook four inches of snow from their bedding.

When the snow ended, temperatures remained cold. A wet, icy slush covered the road and impeded the leading brigade’s progress. Narrow mountain passes “quickly churned into oozing mud as three miles of infantry, cavalry and artillery surged past.” Roads were almost impassable by the time the rear guard struggled to catch up to the column. The slush and mud soaked the men’s feet, intensifying the pain of preexisting blisters and soreness. Many soldiers were in such agony that they removed tight shoes and sat barefoot in freezing weather.

As night fell, the once blustery wind died out completely. As a result, the air quickly filled with the dense smoke of numerous smoldering fires. “Smoke settled like a cloud over the encampment and soldiers ‘could only breath in short gasps.’ Eyes stung and teared when open for longer than a few seconds. Recruits huddled in miserable dejection around acrid campfires, ‘trying to see which side of it will warm without burning.’” Campaign-wise veterans, however, lay with their faces to the ground - the only practical way to escape the smoke.

At 4 a.m. on May 4, the army woke in half-inch ice, but the wintry weather gradually submitted to spring with “trees and bushes beginning to show partial leaves and buds.” The column logged several miles each day through cold and deep creeks, and ”seemingly never-ending, densely wooded hills,” before approaching the foot of Wolf Creek Mountain on May 7. ”This Allegheny Mountain peek soared 1,400 feet above the valley floor and for five hours delayed the advanced infantry brigades.”

The Second Brigade (which included Jacob Bradford) took a turn as wagon and rear guard. “Never a welcome duty, this detail was especially unsavory when crossing a rugged mountain range. Delay after delay beset the rear of the Federal column. As the troops crossed every knoll, the appearance of an even steeper rise repeatedly dashed expectations of reaching the summit. Exhausted soldiers began to believe the mountain to be insurmountable. Finally, with the sun well down in the sky, the wagon train scaled a final pinnacle and paused briefly to survey the vast panorama of surrounding mountains.”

Descending the narrow and winding trail of Rocky Gap was more hazardous than the climb. One member of the rear guard, Ohioan R. B. Wilson, recalled that “the descent was very steep, and the road, in many places hanging over precipices of great height required expert driving and cool nerve.”

As the drivers nervously inched along the treacherous curves, a mule tumbled off the slope, falling many feet to the rocks below. The animal stood “imprisoned among boulders, apparently unhurt” but also beyond rescue. The column had no choice but to march on, abandoning the poor animal to its fate — its ”patient hopelessness…aroused the deepest sympathies of the soldiers.”

Daylight faded to darkness during this final descent, making it almost impossible to see anything. With a sheer cliff on one side of the trail, the other plunged down to rocky Wolf Creek. The only way to negotiate the path was “by painfully keeping to the cliff on one side, and holding on to the tail of the blouse of the man in front.” Finally, as the weary column bumbled around a final turn in the trail, “thousands of campfires burst into view, lighting up gently rolling meadows and fields, while the sky above sparkled with myriad of bright, shining stars.”

Crook’s expedition had finally reached its destination — the southwestern Valley of Virginia nestled between the Allegheny and Blue Ridge Mountains. That evening in camp ”there was an ominous hush over the tented city.” Only two miles separated the Union and Confederate armies. Soldiers checked their weapons and gazed expectantly toward the shadowy heights of Cloyd’s Mountain. Listening to the fading note of Tattoo, the enlisted men knew battle was imminent; Crook and his staff were confident that they would meet resistance the following morning.

The Battle

“The enemy is in force and in a strong position,” Crook remarked after reconnoitering the Confederate position. The battle line stretched half a mile across a series of ridges with dense woodlands on either flank. An open meadow - some 400-500 yards wide - lay at the foot of Cloyd’s Mountain. The Union “would have to traverse a course of rugged terrain, brushy ridges, deep gullies, and icy streams while under relentless fire from two artillery battles on the summit. Next, the Federals would need to ascend the ridge, which in places inclined to sixty degrees, and withstand more than one thousand small arms discharging in their direction. To breach the crest, one also had to navigate formidable breastworks and a species of cheval-de-frise made of rails which had been inverted.”

Crook’s plan of attack was to send the 2nd Brigade (Jacob’s Brigade) to the Confederate right as soon as they heard a signal of ”three successive Federal cannon shots.” The sound of the 2nd Brigade firing would then be the signal for the 1st and 3rd Brigades to attack.

The Brigade’s commanding officer, Colonel White, ordered the 2nd Brigade into the line of battle. The 14th WV was to be on the right with the 9th WV about twenty-five yards behind them. The 12th OH would be on the left with the 91st OH about the same distance behind them.

The Brigade’s commanding officer, Colonel White, ordered the 2nd Brigade into the line of battle. The 14th WV was to be on the right with the 9th WV about twenty-five yards behind them. The 12th OH would be on the left with the 91st OH about the same distance behind them.

Companies “A” and “F” of the West Virginia 14th (Jacob Bradford attached to Co. “F”) were at the forefront of the regiment to act as skirmishers. Commander Colonel Daniel D Johnson temporarily held back the remaining Companies in a deep ravine. When ordered to advance, they moved forward through dense woods and thick underbrush. The Brigade “was soon heavily engaged,” wrote John Holliday of the 91st Ohio, “showing that we had not taken the enemy by surprise. At this point, Regiment after Regiment [was] coming in to action. The roar of the musketry was terrific. So heavy was the firing at this time that in turning to make some remark to Corporal Charley Wolfe who stood by my side, I could not make myself heard by him, although we were standing against each other. The 14th [W]VA on the right could not withstand this terrible storm of lead but turned and retreated in vain.”

“The fight continued at a most destructive range,” Captain Michael Egan of the WV 15th revealed, “as the space dividing the contending forces did not at any time exceed a distance of two hundred yards. This sort of desperate fighting could not last long.”

Colonel Johnson wrote that the regiment “slightly wavered,” but was “promptly rallied by its officers.” He received orders to push forward, being assured that he would be “promptly supported.” The 14th moved onward, firing on the enemy skirmishers. Forced to retreat, the rebels took position behind breastworks at the crest of a hill about 175 yards ahead of the regiment. From that vantage point, the rebels “commanded the entire space between the two lines.” Even so, the 14th ”moved forward steadily, until within twenty yards of the breastworks, where it halted and poured a steady, continuous fire into the enemy’s defensive position.” Colonel Johnson recalled he “could distinctly see a sheet of flames issuing from the rebel works, but could not see a single rebel, so completely were they protected by their defenses.” Being mowed down by fire from an unseen enemy, the regiment “bravely and determinedly” maintained its “exposed and suicidal positions” for half an hour.” The 14th was then ordered forward at the double-quick. Before it could reach that point, the enemy had been routed. Johnson reported the loss of 13 killed and 62 wounded.”

The 12th Ohio took its position on the left of the 14th West Virginia. Colonel Hines wrote in his report that the “enemy were strongly posted on a hill-side behind breast-works of rails, from which they opened fire…On the left, and nearly at right angles with the rail work was a small rifle-pit built of logs.” Gunfire caused a thick carpet of leaves to ignite, setting off a fire line that, in turn burned the fence rail and rifle pit. Captain Wilson, of the 12th Ohio, wrote, “The brilliant battle picture presented at this point, as the line slowly advanced, with colors flying, through the burning woods, pouring in a steady fire, is one that will live forever in the memory of those who witnessed it.” The 12th had to not only face heavy enemy fire, but also advance through burning leaves and logs…and even step over wounded and dead soldiers as the fire engulfed everything in its path. ”The fire presented a picture more revolting than stirring. Wounded soldiers falling amid raging flames cried piteously to their comrades for rescue from a horrible death. Such appeals nearly caused the Union line to waver, but it grimly advanced into stifling Confederate resistance.”

Thus, with the Confederates well hidden behind rail fortifications, the first Union advance of the 14th WV and the 12th OH “ended with both regiments pinned down in highly exposed positions, and being literally shot away.”

The battle reached a murderous peak as frenzied soldiers fought hand-to-hand with muskets, bayonets, knives, and fists; the waters of Back Creek turned red with blood. And although early fighting at Cloyd’s Mountain appeared to favor the Confederates and their strong defensive position, persistent Union attacks eventually broke through, forcing the Confederates to retreat.

The Bridge

Leaving the seriously wounded on the battlefield, the rest of Crook’s men moved toward Central Depot to secure the railroad bridge. Along the way, they destroyed six miles of track, uprooting and setting the ties on fire, the rails twisting in the intense heat.

Leaving the seriously wounded on the battlefield, the rest of Crook’s men moved toward Central Depot to secure the railroad bridge. Along the way, they destroyed six miles of track, uprooting and setting the ties on fire, the rails twisting in the intense heat.

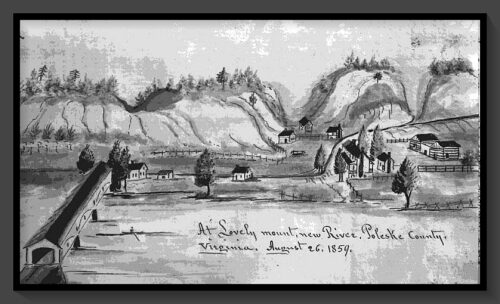

As Federal forces approached the 700-foot bridge that spanned the New River, the outnumbered rebels made one last attempt to defend it. For nearly three hours, an artillery duel raged across the river. But once Confederate fire decreased and their ammunition stores ran low, Union commanders ordered the bridge burned.

Soldiers placed several rail cars loaded with hay inside the covered bridge. Captain Michael A. Egan of the WV 15th recalled that he “got some matches from one of Captain Myers’ men and moved for the bridge immediately. From where I approached the bridge it was necessary to climb some ten or twelve feet up one of the abutment piers to reach the bed of the bridge and get upon it. The structure was a long wooden one, covered with a tin roof. Once up, I broke off some dry pine from the side-works, and ignited the bundle in the west end of the bridge. The weather was dry and warm, with a fresh breeze blowing, and the fire caught quickly and spread rapidly, and soon the whole structure came down with a loud crash in almost as short a time as it has taken me to describe it.”

“Clouds of heavy black smoke rolled out of the ends and poured through every crevice and crack, like a boiler under heavy pressure of steam,” Captain Wilson remembered, “until suddenly the flames burst through, and the bridge seemed to leap into the air from its piers, and plunge, a mass of ruins, into the river below.”

The flooring and tracks of the superstructure were easily destroyed. However, the team lacked the explosives to destroy the foundation piers, and their solid shot canon balls bounced off harmlessly. With the piers intact, the bridge was easily rebuilt; in less than five weeks Rebel trains were again running across the New River.

Image of Bridge, above: 1859 Sketch of Ingles Bridge over the New River by Lewis Miller (Negative image, Montgomery Museum Collection.)

The Hospitals and Prisons

According to The Life of a Civil War Surgeon, from the Letters of William S. Newton, “an assistant surgeon’s responsibility during a skirmish was to prepare for the worst,” Newton, of the 91st Ohio wrote. ”He must get the operating instruments ready and make preparations for the wounded. The hospital could be set up anywhere — a deserted house, barn, tent, or other convenient place.”

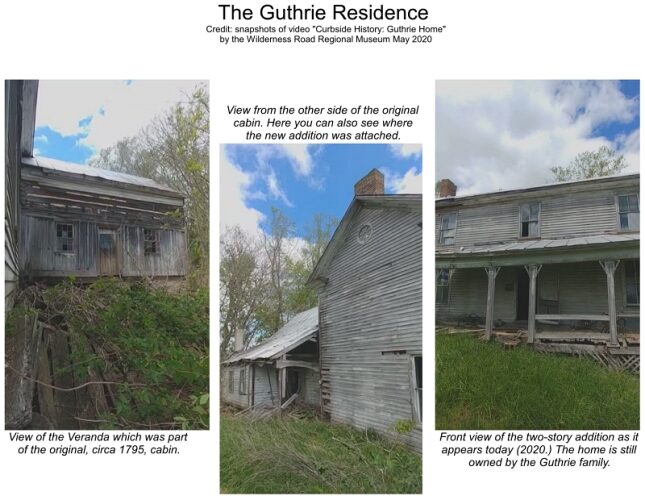

Doctor Neil F. Graham, of the 12th Ohio Infantry, seized buildings owned by James M. Cloyd and Major Joseph Cloyd (aka, Cloyd Farm, Cloyd’s Mansion, or Back Creek Farm) as field hospitals for treating the wounded soldiers. (“Most of the hospital staff treated Confederate and Union wounded indiscriminately. Pathos of suffering and death transcended wartime animosity,” McManus.) Wounded officers, including Confederate Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins, were hospitalized at the nearby John Guthrie homestead, about two miles from Cloyd’s Mountain.

“When the Pennsylvania Reserves finished policing the battlefield for arms and collecting all Confederate prisoners, they left behind only two ambulances, a few stretchers, and limited medical supplies,” McManus wrote. “To transport wounded from the battlefield, Dr. Graham immediately confiscated all available farm carts and fashioned makeshift stretchers from blankets and poles.”

While Crook’s men pursued the enemy to the New River, Dr. Graham, four other surgeons, one chaplain, and twenty-five assistants were left at the battlefield to care for the wounded. Surgeon G. M. Kellogg wrote that after “having been engaged for several hours in collecting our wounded from the field and in attending their wounds, I was ordered to follow the command with all the wounded I could transport. After three or four hours, I was able to follow with over two hundred of the wounded. I left others of our wounded at the field hospital, and still some on the field, with four of our best medical officers, and more than half of my medical and hospital supplies. A number of those left were mortally wounded, and very many required amputation,” later adding, “The report of the character of wounds is incomplete and imperfect.”

It was noon on May 10 before all the wounded were off the battlefield. “Civilians ‘of all ages, sexes, and colors,’ arrived from the surrounding countryside to claim their wounded and dead…Attendants buried unclaimed dead in groups where they fell along the meadow and bluffs…Over 500 injured men packed the Cloyd homes and overflowed into every available barn and outbuilding.” Surgeons utilized a nearby smoke house as an amputating room. A smaller smokehouse served as a dead house. Doctor Graham later recalled, “A more desperately wounded set of men, I never saw.”

Perhaps the scene was similar to one described by Joseph Warren Keifer (Slavery and Four Years of War, Vol. 1-2,) in which he wrote, “I had seen something of war, but, for the first time, my lot was now cast with the dead, dying, and wounded in the rear. A soldier on the line of battle sees his comrades fall, indifferently generally, and continues to discharge his duty. The wounded get to the rear themselves or with assistance and are seen no more by those in battle line. Some of the medical staff in a well organized army, with hospital stewards and attendants, go on the field to temporarily bind up wounds, staunch the flow of blood, and direct the stretcher-bearers and ambulance corps in the work of taking the wounded to the operating surgeons at field-hospital. The dead need and generally receive no attention until the battle is ended.

“I was carried through an entrance to a large tent, on each side of which lay human legs and arms, resembling piles of stove wood, the blood only excepted. All around were dead and wounded men, many of the latter dying. The surgeons, with gleaming, sometimes bloody, knives and instruments, were busy at their work. I soon was laid on the rough board operating table and chloroformed…skilful [sic] surgeons cut to the injured parts, exposed the fractured ends of the shattered bones, dressed them off with saw and knife, and put them again in place, splinted and bandaged. I was then borne to a pallet on the ground to make room for – ‘Next’.”

“Smallpox broke out among the wounded. To isolate these cases, Dr. Graham established a hospital tent midway between the two Cloyd homes. … Attendants buried dead from the hospital near clusters of apple and locust trees on a knoll east of the farm. Sixty to seventy-five graves eventually covered this area.”

Doctor Graham was then called to the Guthrie residence where Confederates Albert Jenkins, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Smith, and Major Thomas Broun lay wounded. He found that Jenkins’ left arm had been shattered near the shoulder by a musket ball. Graham determined the gangrenous arm would need to be amputated. He readied his supplies, moved a kitchen table to the large veranda for use as an operating area, and pressed Mr. Guthrie’s two daughters into service as nurses. But before the surgery could be performed, a squad of Confederate Brigadier General Morgan’s cavalry reoccupied Dublin, captured the field hospitals, and placed the staff under arrest as prisoners of war.

Surgeon William Newton wrote, “They preyed on our hospital as wolves upon a sheep fold. Officers and men depriving our wounded and nurses of all clothing, blankets, etc. that they could possibly lay their hands onto, and in some instances dragging gum blankets from the stumps of recently amputated limbs which had been placed under them for protection of carpets, bedding etc. I have seen them remove these blankets and at once habit themselves with the blood stained trophy, receive commendation for this heroic deed from their companions in arms, who have been guilty of like atrocities. I also heard this conduct represented by a Rebel surgeon who happened to be more humane, to his Genl, and asked if he countenanced such treatment. The Genl replied yes, and with an oath said he approved of it all, and more he hoped few of the D—-d Yankees there wounded would ever live to see their homes again.” (Gallipolis, OH, October 8, 1867 - William S. Newton Manuscript Archives.) ”They took everything, including surgeons’ tools dripping with warm blood and forced the breathing to march.” Newton continued, “Before the ordeal was over, the graves of dead soldiers were dug up and everything of value was removed.”

According to the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (June 4, 1864) Dr. Graham confirmed that Morgan had permitted his men to disinter the bodies of Union soldiers and strip them of their clothing. He said, “the conduct of the rebel General John Morgan was that of a ruffian.”

Morgan’s surgeons arrived at the Guthrie house on May 13 and seized Graham’s blanket, oil cloth, and instruments. They planned to perform Jenkins’ amputation themselves. However, the general ordered them away and requested Dr. Graham perform the operation as the two had originally arranged. The Federal doctor had to ask to borrow his own equipment back for the operation, to which the Confederate surgeon, “bubbling over with professional courtesy, generously acceded.”

Jenkins was removed to another location to recuperate, attended by his own medical surgeons, his wife and mother-in-law. In the days that followed, whether a “consequence of a lack of attention or a lack of competency on the part of the rebel surgeons, a secondary hemorrhage took place.” Jenkins bled to death on May 24*.

“The Confederate soldiers took over the treatment of all wounded,” explained the Wilderness Road Regional Museum. “[They] sent some south on rails to POW camps and kept the most gravely wounded to tend to. There is a mass burial area mentioned for both Union and Confederate soldiers that died on the field or in local makeshift hospitals, [but there is] no record on names. Some we find from letters and reports.”

McManus wrote, “When Morgan’s cavalry departed, a detachment of home guard troops took charge of Cloyd’s farm. After Jenkins’ death, little time was lost dismantling the Federal field hospital. Officials transported wounded to Emory and Henry Hospital in Danville and dispatched Union surgeons and attendants to Southern prisons,” including Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio, Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia and Andersonville Prison in Andersonville, Georgia.

Final Thoughts

Precisely where Jacob Bradford was throughout all of this remains unknown. My guess is that he was too seriously injured to ever leave the field hospital at Cloyd Farm where he was arrested, died, and likely buried in an unmarked grave. But it is only a guess. There is simply too much contradictory “evidence” among all the sources of information to come to a satisfactory conclusion.

Precisely where Jacob Bradford was throughout all of this remains unknown. My guess is that he was too seriously injured to ever leave the field hospital at Cloyd Farm where he was arrested, died, and likely buried in an unmarked grave. But it is only a guess. There is simply too much contradictory “evidence” among all the sources of information to come to a satisfactory conclusion.

As an example of similar contradictions, my research (military records, newspaper articles, soldier’s diaries, etc.) on the well-known Confederate General Albert Jenkins revealed: He died at Cloyd Mountain, or at the Guthrie home, or at a home in the Belspring area. He died of pneumonia, or of hemorrhage when an orderly accidentally knocked off a ligature, or of a wound to the abdomen. He died on May 19, or May 21, or May 24.

Newspapers reported that Jenkins had been captured and killed. Then they retracted that statement, proclaiming he had not been captured and was, in fact, alive and well. Oddly, the actual date of his death* is perplexing. The historical monument in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania reads May 24. However, his grave marker in Huntington, West Virginia reads May 21. (The differing dates are submitted as fact hundreds of times - even among the most respected historians.)

Despite the errors and omissions, we now have a greater awareness of the little-known battle that took Jacob Bradford’s life. We can imagine him excitedly volunteering for the cause. We can imagine how quickly that excitement turned to exhaustion, then fear. And we can imagine the horrors and sacrifices of our ancestors’ family, friends, and communities. It’s important that we remember them.

McManus wrote, “Ardent and pugnacious when the campaign began, soldiers of both armies mellowed quickly after the blood bath at Cloyd’s Mountain. Recruits matured into veterans, and veterans grew increasingly weary of sorrow, suffering and death. The subsequent campaign blurred into a wretched picture of fatigue, hunger, and misery.

“In the weeks that followed, new faces replaced memories of dead comrades; new warfare drilled vivid reminiscences of the spring campaign. The May 1864 expedition against the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad was a relatively insignificant excursion within a highly eventful war. It caused no momentous historical repercussions, and it contained no lofty maxims. Overshadowed by larger armies and more consequential campaigns, it failed to receive public recognition. Nevertheless, the courage and vivacity, the suffering and despair, of the Civil War soldier emerge as vividly from Cloyd’s Mountain and the New River Bridge as from Gettysburg and Appomattox.

“Through the years, most of the men who marched, fought and died in this campaign have been forgotten. Now, only the mountains remember.”

Announcements

-

Submitted by Mike Spiker – Due to continued COVID restrictions, we will not reschedule the Family Reunion for this year.

-

Submitted by Kate Spiker – With the current restrictions and guidelines due to covid-19, we have decided to move the Spiker Bull Ride to October 2nd and 3rd, 2020. We hope to incorporate all of our activities at that time and look forward to seeing you then!

-

Submitted by Bobbi Spiker Conley – Do you remember our story last January about Buckner Zinn and the tortoise? We added a follow-up to the article asking about a possible connection to a 13-year-old boy from Washington County, PA. The boy, now grown, replied to our inquiry. See his response in the January edition (scroll to bottom of that page.)